By Luisa Salomón y Salvador Benasayag

Venezuela does not meet the public health criteria set by the World Health Organization to ease lockdown restrictions safely. Based on official figures, we found that Venezuela does not meet the WHO’s main five criteria, nor does it report information about the other 19 indicators. Prodavinci estimates that the day before lockdown restrictions were lifted, the number of new confirmed cases grew by a factor of six, compared to the three previous weeks. Authorities fulfilled only 5,74 percent of the WHO testing standard of one thousand tests per million people per week.

After two-and-a-half months of quarantine, Venezuelan authorities approved a plan to ease restrictions and resume activities in eight economic sectors, starting June 1st. They called it “the Venezuelan method,” a model that alternated five work days followed by a 10-day quarantine. By the end of the first week, they changed the “method” to one work week followed by one week of quarantine.

There isn’t a manual that guarantees reopening without contagion, but the World Health Organization (WHO) published a general strategy with 24 public health criteria that countries should meet in order to ease lockdown restrictions safely.

Venezuelan authorities did not have the epidemic under control when quarantine restrictions started to be lifted, Prodavinci found. There were not enough PCR diagnostic tests and the authorities were not publishing enough data to evaluate the situation. Experts consulted by Prodavinci point out that the country’s healthcare system does not have the capacity to cope with rising COVID-19 cases.

Venezuela accumulated 5,832 confirmed cases in 110 days, recorded between the announcement of the first two cases and June 30. The country doubled its number of confirmed cases in 17 days.

Between the start of the national quarantine and the day prior to the easing of restrictions, the seven-day moving average of new daily confirmed cases rose 671.81 percent. This indicator remained below 15.29 daily new confirmed cases until May 16. One month and a half later, on June 30, it went up to 235.14, the highest record since cases were first reported.

Authorities started lifting lockdown restrictions, but 20 days later, they stopped the process in 12 states. The number of new confirmed cases had tripled and the number of deaths quadrupled. They justified new restrictions as a response to a “new outbreak” in Venezuela.

Using official data and taking the WHO’s guidelines as a reference, we explain why Venezuela did not meet the recommended criteria for easing lockdown restrictions.

1. Venezuela did not have the epidemic under control when the easing of lockdown restrictions started

The WHO has established epidemiological criteria to evaluate the advance of epidemics and whether it is possible to safely reopen the economy. The first criterion is the continuous decline of cases: three weeks after the latest peak, the number of confirmed cases must have decreased at least 50 percent. After those three weeks, there must be a sustained decrease in confirmed and probable cases, all cases presenting symptoms similar to COVID-19’s.

The day before reopening Venezuela, on May 31, only seven days had passed since the last peak of new cases. The moving average of new cases was also on the rise. Three weeks before, there was an average of 8.71 new cases registered daily. On May 31, the average was 55.57 new cases: An increase of 537.70 percent.

2. Cases of communitary transmission were rising before the easing of lockdown restrictions

After three months of quarantine Venezuela’s official reports still include imported cases, but they also show an increase in the number of communitary transmissions. If we only take into account the daily report of new communitary cases, the most recent peak occurred only two days before reopening began. In the two weeks prior, the daily average of new communitary transmissions went from 4.43 to 18, an increase of 306.32 percent.

Since the first confirmed COVID-19 infection, Venezuela entered the first phase of transmission with sporadic cases, according to the WHO’s standards. After 27 days, on April 8, Venezuela registered 167 new confirmed cases. According to the WHO, this signaled a new phase: the virus began spreading through transmission clusters. On May 22, Venezuela reported 1,010 confirmed cases in 71 days. The WHO placed the country in another category: nations with communitary transmission.

3. Venezuela was not doing enough PCR diagnostic tests

COVID-19 diagnosis protocols in Venezuela establish the use of two kinds of tests: the Polymerase Chain Reaction tests, known as PCR, and the serologic tests, also known as “instant tests.” But the latter should not be used to diagnose the disease, according to the WHO. Venezuelan authorities report the total amount of tests made in the country, without specifying how many are serologic tests and how many are PCR tests.

In their May 2020 report, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs stated that Venezuela made 16,577 PCR tests in the last three months, equivalent to 574 tests for every million inhabitants.

To measure the extent of the epidemic, the WHO establishes that less than 5 percent of PCR tests should be positive in a span of two weeks. A high percentage of positive results suggests that not enough testing has been done. This indicator can only be taken into account if the country does at least 1,000 PCR tests for every million inhabitants every week.

Until May 21, Venezuelan authorities did 574.19 tests for every million inhabitants. Since the first confirmed case and up until that date, Venezuela should have done at least 10,000 tests for every million inhabitants, according to WHO’s standards.

4. Venezuela does not publish enough data to assess the viability of easing lockdown restrictions

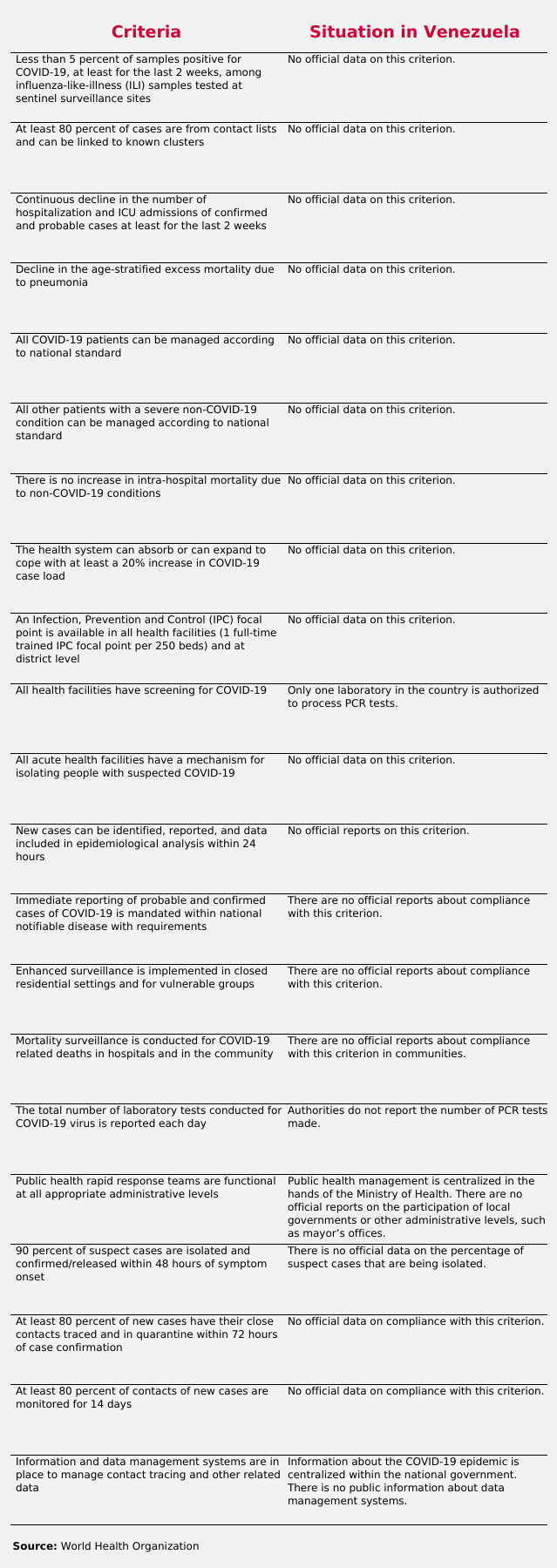

Venezuelan authorities only report information about five of the 24 epidemiological and public health criteria set by the WHO to determine if a country is ready to ease restrictions.

These are the 19 criteria without public reports:

****

This story is part of a broader series about the easing of quarantine restrictions in Venezuela. The series includes explanations about the healthcare system’s preparation and capabilities for surveillance and tracing. Read the detailed version of this story in Spanish here.

Credits

Editors: Ángel Alayón, Oscar Marcano, Valentina Oropeza and Helena Carpio

Graphic design and infographics: John Fuentes

Tableau dataviz: Salvador Benasayag

Photography: Gaby Oráa | RMTF

Translation: Flaviana Sandoval